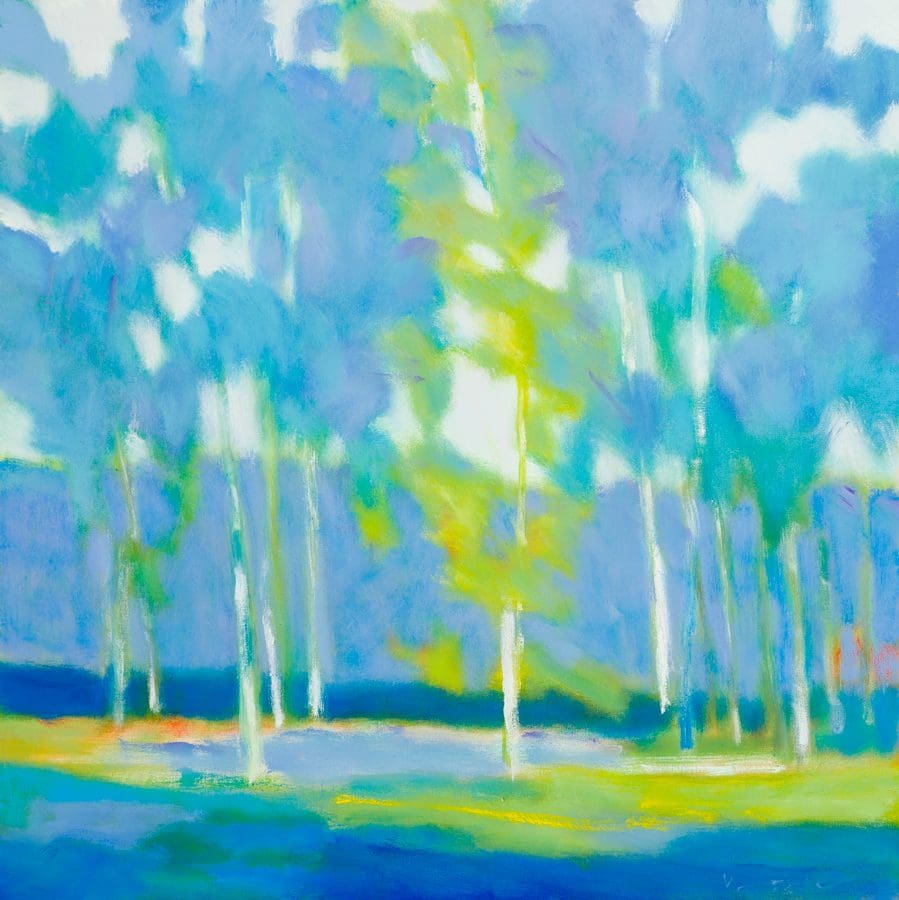

Based in Montana, Marshall Noice gathers inspiration from the majestic landscape around him. Noice avoids a literal translation of his surroundings, despite his background as a photographer. Instead, he captures the spirit of the landscape through expressive color and light. Read our conversation with Noice to learn more about his active process, his evolution from black and white to vivid color, and his idea of the perfect painting.

“I believe that when someone is viewing a work of art, they bring their own experiences, memories, and preferences to the process of looking at that painting. At that point I’m no longer involved. It’s a conversation between the viewer and the art.”

How do you balance abstraction and representation in your work?

MN: I like to look at my work with the intention of creating something that would function if all of the references to the landscape were eliminated. If there is a line, and it doesn’t read as a tree trunk, or if there is a shape, and it doesn’t read as a hill, I want to make sure my piece is still fully functional.

My idea of a perfect painting—and it’s one that I occasionally get closer to, but have never quite gotten there—is one where the viewer is fully engaged with all of the painterly aspects of the work: light against dark, thick against thin, and warm against cool, regardless of the subject matter. It’s a painting where the subject matter and everything but the subject matter are on a teetering edge, fighting for dominance in the artwork.

What is your studio space like, and how does it affect your process?

MN: My studio is in the back of a main street business in the little town of Kalispell, Montana. The building was built in 1899 by a local brewing company. It was the silver dollar saloon, and I work in what used to be the kitchen.

I think it does have an affect on the work that I do in that it has very high ceilings, and I can get some distance from my paintings, which I do quite frequently. I always stand when I work, and I’m just constantly walking back and forth. I have a huge pegboard wall that I put work on when I paint, and then I have an even larger pegboard wall on an adjacent wall where all of my in process paintings are keeping me engaged. My painting process is very active, and I think that the opportunity to not paint in a closet—being able to get away from the piece and having quite a bit of space around the painting itself—allows me a freer approach to painting.

You used to be a black and white photographer, and now you paint vividly colored landscapes. Can you discuss how this evolution came about, and the role that color plays in your work?

MN: My life as a black and white photographer is integrally related to my life as a painter of brightly colored landscapes. I learned a lot about the landscape and about composition by working with a large format view camera, and interacting with the landscape in that rather limited fashion for a number of years.

All the time I was engaged in photography I was still painting. Painting was always part of the process, and photography was just another part of it—another way of interpreting the world. I was extremely fortunate to spend a summer working as Ansel Adams’ assistant, and I often think of what I learned from him when I’m working on a composition. So the experiences I had as a photographer still have an impact on my work today, even though it was over 30 years ago.

The transition from black and white to color occurred after seeing a body of work by another Montana painter, Theodore Waddell. I really responded to his brightly colored, expressionistic paintings of landscapes and animals. And I thought, “Wow, I would just love to paint like that.” It opened the floodgate to big color as opposed to more literal color, which had been my approach to painting in the past. Back then my work was much more representational, and the color was not nearly as bombastic as my color is today. So I kind of got permission from him to move in that direction. These days, for me it’s really all about color. The painting and the subject matter is sometimes just an excuse to experiment with color.

What do you hope others see in your work?

MN: I honestly don’t have specific expectations regarding what others see in my work. I hope that my work is engaging enough that they will stop, look, and maybe have a conversation with the painting. When I am creating a piece, I’m having a conversation with that painting during the art making process. Then when the painting is done, it typically goes off to a gallery or a museum and starts to live a life of its own.

I believe that when someone is viewing a work of art, they bring their own experiences, memories, and preferences to the process of looking at that painting. At that point I’m no longer involved. It’s a conversation between the viewer and the art.

What are sources of inspiration for your work?

MN: Inspiration is really easy for me to come up with, because I’ve been blessed with intense curiosity. I can get going on a painting really easily. It can be as simple as a “what if?” question. What if all of those colors that are cool were warm? What if I put a complementary color next to that color? Those sorts of questions are enough for me to start a painting.

If I get to the point where I really don’t know what I feel like painting, I’ll just go for a walk. Oftentimes I will see something—whether it’s a horizon line, or the way the light is coming through the trees, or the color of the sky—and that’s all I need to get back into the studio and start a painting. So inspiration is never difficult for me to find. If anything, I struggle with having too many ideas for paintings simultaneously!

Visit the gallery closest to you to see more of Marshall Noice’s work.